From Handbags to Power Plays

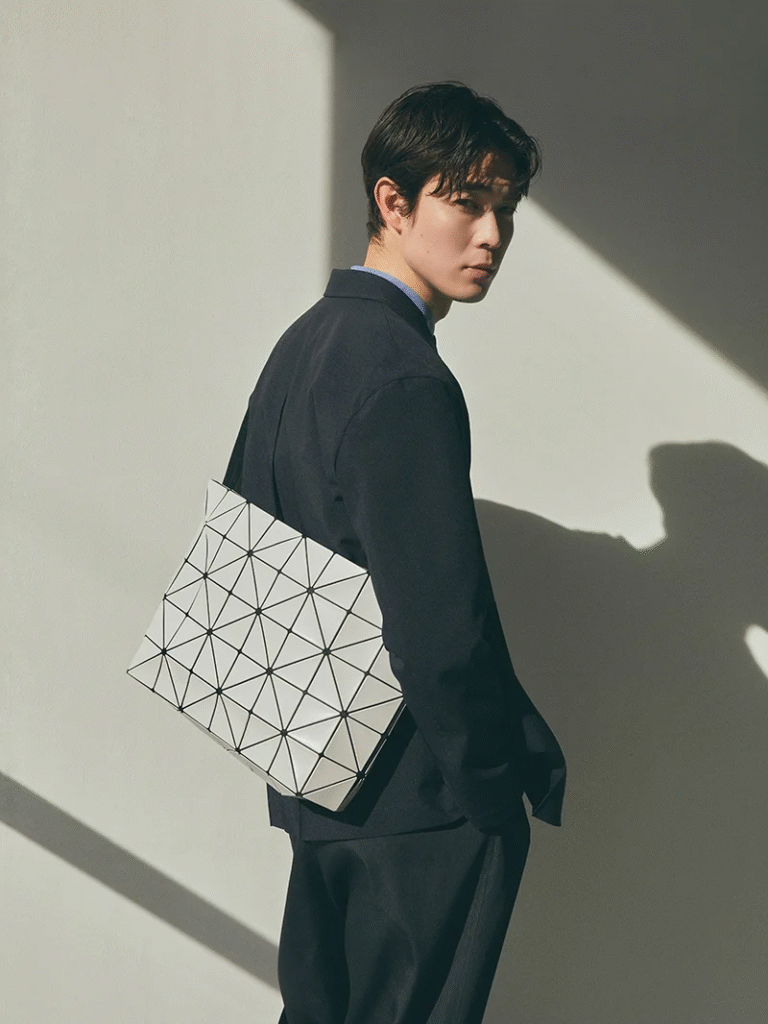

For most people, a handbag is far more than just a utilitarian object to carry essentials. It is a personal statement, a daily companion that blends form and function, reflecting the owner’s taste, status, and personality. From the buttery leather of a Hermès Birkin to the geometric shimmer of an Issey Miyake Bao Bao, handbags occupy a unique space in fashion: they are both wearable art and cultural symbols.

In the present social media culture, certain handbags have transcended their role as accessories to become icons in their own right. They cameo in films, shape social media trends, and often command waiting lists that stretch for years. A celebrity sighting with a rare design can spark an instant surge in demand, while vintage models fetch staggering prices at auctions. In this way, the handbag has evolved into a marker of identity, aspiration, and even investment value. But in an industry where imitation is both a form of flattery and a billion-dollar business, how do brands protect these intangible yet highly valuable assets?

The answer lies in the nuanced, and often underexplored, realm of intellectual property (IP) protection for fashion patterns. While trademarks for brand names and logos are well understood, the idea that a pattern itself can serve as a trademark is still a developing area of law. And this is where things get interesting. Unlike patents or copyrights, which protect functional or creative works, a pattern trademark straddles a delicate balance: it must be distinctive enough to signal source, yet not so generic that it monopolises basic design elements.

This blog unpacks how fashion houses navigate the tricky legal terrain of protecting patterns, with a deep dive into some case studies, culminating in one of the most fascinating recent disputes, the “Bao Bao” Issey Miyake case, which perfectly illustrates both the power and the pitfalls of pattern trademarks. Along the way, we’ll look at the methods courts use to determine distinctiveness, how different jurisdictions treat the issue, and why the fashion industry’s fight against copycats is as much about brand identity as it is about aesthetics.

Understanding Pattern Trademarks

When most people think of trademarks, they imagine logos or brand names that identify the source of goods or services. However, pattern trademarks belong to a fascinating category known as non-traditional trademarks, where the visual design itself serves as a powerful source identifier. In the fashion world, patterns aren’t just decorative elements; they can become symbols that consumers instantly associate with a specific brand.

A pattern trademark is essentially a recurring design or motif consistently used on products that functions as a source identifier for consumers. Unlike conventional trademarks, which protect names or logos, pattern trademarks protect the aesthetic features that distinguish one product from another in the marketplace. For many luxury fashion brands, these patterns become badges of origin, guiding consumer choices even without the presence of any explicit text or logo.

It’s important to understand how pattern trademarks differ from other intellectual property protections like design patents, copyright, and trade dress. Design patents cover the ornamental design of a product for a limited period but do not protect brand identity or source recognition. Copyright protects original artistic works but usually excludes functional or mass-produced industrial designs, particularly in fashion, where originality standards are quite stringent. Trade dress, on the other hand, covers the overall look and feel of a product or packaging, including shape, color, and design elements, but typically requires proof that the design has acquired distinctiveness and is non-functional. Pattern trademarks uniquely protect specific designs/motifs/elements that serve as brand identifiers rather than merely ornamental or functional features.

Fashion brands invest heavily in protecting their patterns because they represent more than aesthetic appeal; they embody the brand’s identity and heritage. Securing trademark protection allows brands to prevent unauthorised copying by competitors and fast fashion retailers, reinforce consumer loyalty, and preserve the commercial value of their design assets over time. Take the example of Burberry’s check, introduced in the 1920s, which evolved from a coat lining into a global status symbol, fiercely protected through trademarks, litigation, and controlled distribution.

Globally, the legal recognition and enforcement of pattern trademarks vary, reflecting different cultural and legal traditions. In the European Union, the Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) applies strict standards for inherent distinctiveness but permits protection through acquired distinctiveness, as seen in notable cases involving Prada’s triangle pattern and Louis Vuitton’s Damier design. In the United States, the Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has granted registrations for pattern trademarks like Bottega Veneta’s intrecciato weave, carefully balancing issues of functionality and distinctiveness. Meanwhile, the Japan Patent Office tends to take a conservative stance, especially when patterns resemble traditional motifs, limiting protection when consumers do not perceive the pattern as indicating a particular source. Although pattern trademarks are less litigated in India, rising IP awareness and globalization suggest that Indian brands are increasingly interested in protecting unique fashion designs, mirroring global trends.

Protecting Pattern Trademarks- The Legal Landscape

Protecting a pattern as a trademark, especially in the context of handbags, is no straightforward task. To be registrable, a pattern must satisfy several legal requirements that ensure it functions as a true identifier of the product’s source, rather than merely serving as decoration or a functional feature.

First and foremost, distinctiveness is crucial. The pattern must be capable of distinguishing the goods of one producer from those of others in the minds of consumers. This can be inherent, where the pattern is unique or unusual enough to immediately signal its origin, or acquired through extensive use and promotion, known as secondary meaning. For handbag patterns, proving inherent distinctiveness is often difficult because many designs incorporate common motifs or elements widely used in the fashion industry.

Another significant hurdle is the non-functionality doctrine. Trademark law does not protect features that are essential to the product’s use or that affect its cost or quality. In handbags, certain patterns might be considered functional if they provide structural benefits, improve grip, or serve some utilitarian purpose. For example, a weave that strengthens the bag might be deemed functional and thus excluded from trademark protection, even if it also acts as a source identifier.

Proving acquired distinctiveness is frequently the most viable path to protection. This involves demonstrating that consumers have come to recognize the pattern as a symbol of the brand. Brands must provide substantial evidence, such as advertising expenditures, sales figures, consumer surveys, media recognition, and instances of copying by competitors, to convince trademark offices and courts that the pattern functions as a trademark. This evidentiary burden is often high and requires a sustained commitment to marketing and brand-building.

The Bao Bao Issey Miyake Dispute

The Bao Bao collection by Issey Miyake is renowned for its innovative approach to handbag design. Since its debut in 2010, the line has captured attention through its distinctive geometric tessellation: a pattern of interconnected triangles that shift and reshape as the bag moves. This design is more than just decoration; it transforms the silhouette dynamically, creating a unique visual and tactile experience that has become synonymous with the brand.

However, this unmistakable pattern found itself at the center of a significant legal dispute when Largu Co., Ltd., a Japanese company, began marketing a range of bags under the brand “Avancer” featuring a strikingly similar tessellating triangular design. Though the defendant’s triangles were not always exact rectangular equilateral shapes, the overall visual effect (shifting three-dimensional forms) was close enough to prompt claims of infringement under Japan’s Unfair Competition Prevention Act.

The main question that arises is whether Bao Bao’s pattern serves merely as an ornamental or aesthetic feature, or has it transcended this role to become a recognisable source identifier for Issey Miyake’s bags? The Tokyo District Court carefully analysed this issue, weighing evidence of the pattern’s distinctiveness and consumer recognition. The court recognised the uniqueness and innovation of Bao Bao’s design, acknowledging that its three-dimensional triangular tessellation is far from a common decorative motif. Importantly, the court accepted that this design had acquired a significant reputation and popularity among consumers by the time Largu introduced its products, reinforcing its status as a source indicator.

The defendant’s argument, that the differing shapes of triangles negated the likelihood of confusion, was dismissed. The court emphasized the overall visual impact and how consumers perceive the design in context, rather than dissecting individual geometric elements. It also ruled that the substantial price gap between the products was irrelevant in assessing consumer confusion, as recognition and association with the Bao Bao brand prevailed regardless of cost.

Ultimately, the court issued an injunction against Largu, halting further sales of the infringing bags, and awarded damages exceeding 71 million Japanese yen to Issey Miyake. Notably, the court did not find grounds for copyright infringement, observing that the bags’ mass-produced nature and industrial design characteristics placed them outside the scope of copyright protection. In Japan, copyright law distinguishes between works of pure artistic expression and applied art that is inseparably tied to a product’s functional use. Since Bao Bao bags were produced in large quantities and their geometric design directly shaped the bag’s structure, the court treated them as an industrial design, better suited for protection under design law or unfair competition, rather than as independent creative works of art.

The Bao Bao case highlights the critical importance of securing protection for distinctive design elements that function as source identifiers, especially in the fashion industry, where imitation is common. The case also exemplifies how courts may balance aesthetic innovation against consumer perception, underscoring the need for brands to build and document strong reputational evidence if they wish to enforce design-based rights successfully.

Other Notable Cases

The fashion industry is rife with iconic patterns that have become emblematic of brand identity, yet protecting these visual trademarks often invites fierce legal challenges worldwide. While Bao Bao’s case was a landmark for geometric innovation, recently other brands have faced their battles to safeguard signature patterns.

Bottega Veneta’s intrecciato weave pattern trademark application was initially rejected by the USPTO as aesthetically functional, since woven leather is common in handbags. To overcome this, Bottega narrowed the claim to a specific configuration, uniformly sized strips woven at a 45-degree angle, and submitted extensive evidence of acquired distinctiveness. This included substantial advertising, consumer surveys, and sales data proving that the weave was widely recognized as a source identifier. The TTAB accepted that the design had moved beyond mere ornamentation, granting registration. The case highlights how precise definition and strong proof of secondary meaning are essential for protecting pattern trademarks.

Naghedi’s neoprene weave trademark battle highlights the challenges faced by emerging brands in securing protection for pattern marks. The USPTO initially refused registration, citing the weave’s ornamental nature and its prevalence in the industry, unlike Bottega Veneta’s narrowly defined weave with strong secondary meaning. In response, Naghedi argued acquired distinctiveness through over a decade of exclusive use, rapid sales growth ($600,000 in 2021 to $16 million projected in 2024), $2.5 million in recent advertising, celebrity endorsements, and competitor copying. Still, procedural objections, such as whether a swatch drawing suffices or multiple marks exist, underscore systemic hurdles newer fashion brands face.

Beyond the Verdicts

While the Bao Bao case marks a significant step forward in recognizing the protectability of geometric handbag patterns under unfair competition law, it simultaneously exposes critical gaps in current trademark doctrine that merit reconsideration. The court’s reliance on visual distinctiveness and consumer recognition rightly acknowledges the communicative power of such patterns. However, the judgment stops short of fully addressing the underlying issue of functional aesthetics: how to draw a principled line between an ornamental feature that drives commercial success and one that genuinely signals source. This ambiguity leaves emerging designers vulnerable to copycats and risks creating inconsistent standards across jurisdictions.

To move beyond this legal limbo, future discourse should push for a more nuanced, multi-factor test that explicitly integrates cultural and design innovation considerations alongside traditional distinctiveness analysis. Additionally, courts and trademark offices must develop clearer guidelines on how to assess the “three-dimensional dynamism” of patterns, like Bao Bao’s tessellations, that alter in appearance with use, distinguishing them from mere background decoration. Embracing such complexity not only offers stronger, more predictable protection for creative handbag designs but also better aligns intellectual property law with the realities of contemporary fashion.

![A Blair Waldorf standalone is in the works !!!! The Queen of Upper East Side is going to have a sequel of her own, with the focus completely on her !

Like she deserves 🫶🏻🙇🏻♀️✨

What is your favourite Blair Waldorf moment from Gossip Girls ?

[Blair Waldorf, Gossip Girls, Sequel, Iconic, Pop Culture, Quotes, Icon, Queen Bee, Let The Raven Talk]](https://lettheraventalk.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)