Too often, we hit the play button only to realise that what we thought was the video of our favourite classic is in fact another series hiding under the same title. This trend of clickbait culture has raised questions, including that of consumer deception and filmmakers’ rights. The practice of recycling film titles to ride on the nostalgia factor further highlights the broader picture about originality and the extent to which titles can be protected as an intellectual property right. A recent Bombay High Court ruling in Sunil S/O. Darshan Saberwal vs Star India Private Limited And Ors. illustrates why claims of copyright infringement might not be the best way to approach the court for protection in such cases.

The LOOTERE Title dispute: Mere registration of titles with producers’ association isn’t a guarantee of legal protection

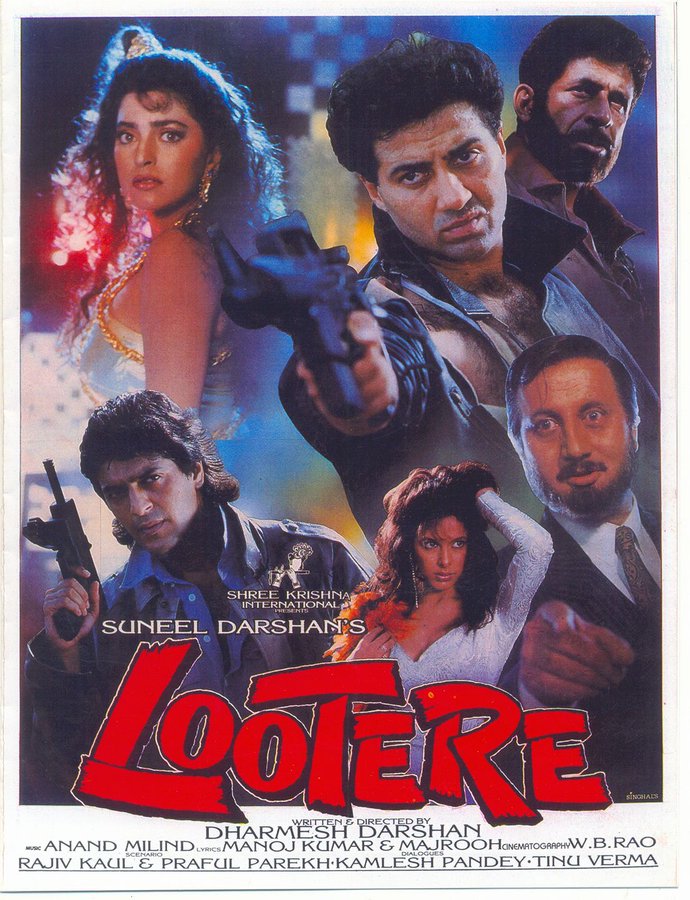

In Sunil S/O. Darshan Saberwal vs Star India Private Limited And Ors., the suit was filed by the plaintiff , Sunil S/o Darshan Saberwal, a film producer operating under the proprietary name Shree Krishna International, who produced a Hindi feature film titled ‘LOOTERE’, seeking to restrain Star India Private Limited from producing and releasing a web series using the same title. The plaintiff asserted copyright claim over the film title ‘LOOTERE,’ noting its registration with the Western India Film Producers Association, and renewal thereafter, and subsequent registration by the Deputy Registrar of Copyrights for the cinematograph film in his name. It was also pointed out that title registration for ‘LOOTERE’ had also been secured across Feature Film, TV Serial, Web Series, and Web Film categories. However, Star India contended that there cannot be copyright in a mere film title. It further noted that registration of film titles with the film producers’ association are merely in the form of private arrangements, carrying no statutory force. The defendant also noted in its arguments that recycling of film titles is a common industry practice and is permissible as long as the underlying content of the films differs. Additionally, the defendant argued that the plaintiff had “whiled away substantial amount of time” in filing the case, as the suit had been filed two years after the plaintiff noticed the official trailer of web series ‘LOOTERE’ on an OTT platform, and sent their first communication to the broadcasting channel and associations on 9 September 2022. The defendant contended that this delay alone was a valid ground for denying the injunction.

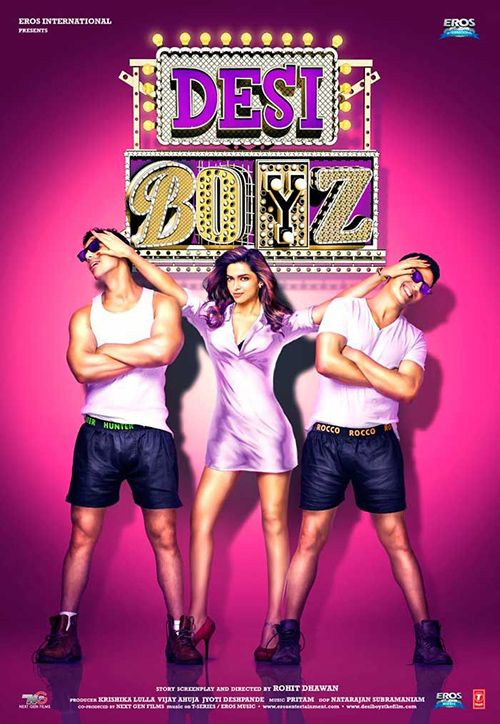

The court upheld the defendant’s argument that copyright cannot subsist in film titles, as a title being incomplete in itself cannot qualify as “work” under Section 2(y) of the Copyright Act nor as “literary work” under section 13 of the Act. The Court referred the judgment in the case of Krishna Lulla and Others Versus. Shyam Vithalrao Devkatta and Another where the apex court had refused to extend copyright protection to the title “Desi Boys” stating that the combination of these two words lacks originality and literary character. Similarly, the word “Lootere” was used in common parlance to refer to thieves and robbers. Further, it was clarified that registration of titles with film producers’ associations does not create any statutory rights and are merely in the form of private contractual agreements, that could be enforced through internal arrangements qua the members. Since Star India was not a member of the producers’ association, no action was possible. Additionally, it was found that the plaintiff’s prayer for temporary injunction had become largely infructuous since the web series had already been streaming online since March 22, 2024. It is imperative to note that the contents of the two works were found to be completely different; the plaintiff’s film is a love story, whereas the defendant’s web series is about the hijacking of an Indian ship, leading to a battle between the pirates and the ship’s crew. The court concluded that the plaintiff had failed to satisfy the triple tests of prima facie case, i.e. there was no irreparable loss being caused to the plaintiff by the usage of the title “Lootere” by the defendants for their web-series, and the balance of convenience did not lie with the plaintiff thereby declaring the title to be fit to be used by the defendants.

Choosing the right approach: Copyright, Trademark and Passing off

Section 2 (y) of the Indian Copyright Act defines the term “work” to mean and include “literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works, cinematograph films, sound recordings, works of joint authorship and works of sculpture includes casts and models”. Section 13 further delineates the classes of works in which copyright can and cannot exist, providing ‘originality’ as an important prerequisite. As book and film titles are expressions that are too short to show any literary or original quality, they are generally not extended any copyright protection. In such cases, creators often move to register a trademark for the title.

According to Clause 2(zb) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, a trademark is “a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours”. This is inclusive of words, logos, colour combinations, signatures etc. Section 7 of the Act states that classification has to be done by the registrar in accordance with “International classification of goods and services for the purposes of registration of trade marks.” Within the Nice Classification established by the Nice Agreement (1957), trademark applications are divided into 45 classes, Classes 1 to 34 for goods and Classes 35 to 45 for services. Entertainment services fall under Class 41, covering activities like film production. Trademark protection for film titles are generally sought under class 41. However, as a routine practice, applications for trademarking titles of film series tend to succeed much more than standalone films. This was also confirmed by the ruling in Kanungo Media (P) Ltd v RGV Film Factory where the court observed that while protection is certain for titles of film series, the same treatment may be given to titles of single films only if the particular term has acquired a “secondary meaning” with the audience invariably associating the title with the claimant’s work. Certain parameters were laid to determine if the work has acquired secondary meaning including: (a) the length and continuity of use; (b) the extent of advertising and promotion and the amount of money spent; (c) the sales figures on purchases or admissions and the number of people who bought or viewed the work; and (d) the closeness of the geographical and product markets of the plaintiff and defendants.

Another legal remedy in such cases lies in “passing off” actions. In passing off, the law views reputation as an “incorporeal piece of property” entitled to protection. To succeed in such claims, the claimant must satisfy the trinity test of goodwill, misrepresentation, and resulting damage. In such cases, courts look into the “likelihood of public deception. Reputation and distinctiveness of the title are also major considerations. This has to be evidenced by consumer recognition as held in Anil Kapoor Film Co Pvt. Ltd. vs Make My Day Entertainment & Anr. In this case, the plaintiffs, whose movie titled “Veere Di Wedding” (which was to star Sonam Kapoor and others), which was still under production, made passing off claims against the defendant’s film titled “Veere Ki Wedding”, which was completed and set to be released. The plaintiff argued that he had registered his script titled “Veere Di Wedding” with the Film Writers’ Association (FWA) in March 2015 and the film title of his movie was successfully registered with the Indian Film and Television Producers’ Council (IFTPC) by June, 2015. The plaintiff also highlighted his promotional efforts through newspapers.

The court, however, was not impressed. Citing Kanungo, the decision noted that titles cannot be used to “by a junior user in such a way as to create a likelihood of confusion of source, affiliation, sponsorship or connection in the minds of potential buyers.” Even unreleased works may be protected, if sufficient amount of pre- release publicity is shown. This required proof of active advertising by the plaintiff and not just third-party reports like newspaper reports. In the information age, public is more aware which makes deception harder, hence bar to allow a claim for “passing off” must be set high. The plaintiff’s pre- production expenditure was found to be “singularly underwhelming” as evidence and therefore, the injunction was denied.

Similarly, descriptive nature of the term “Illusionist”, use of the term in an earlier film title, no similarities so as to cause public confusion between the films in contention were factors considered to reject a claim for temporary restraining order by a Los Angeles federal judge.

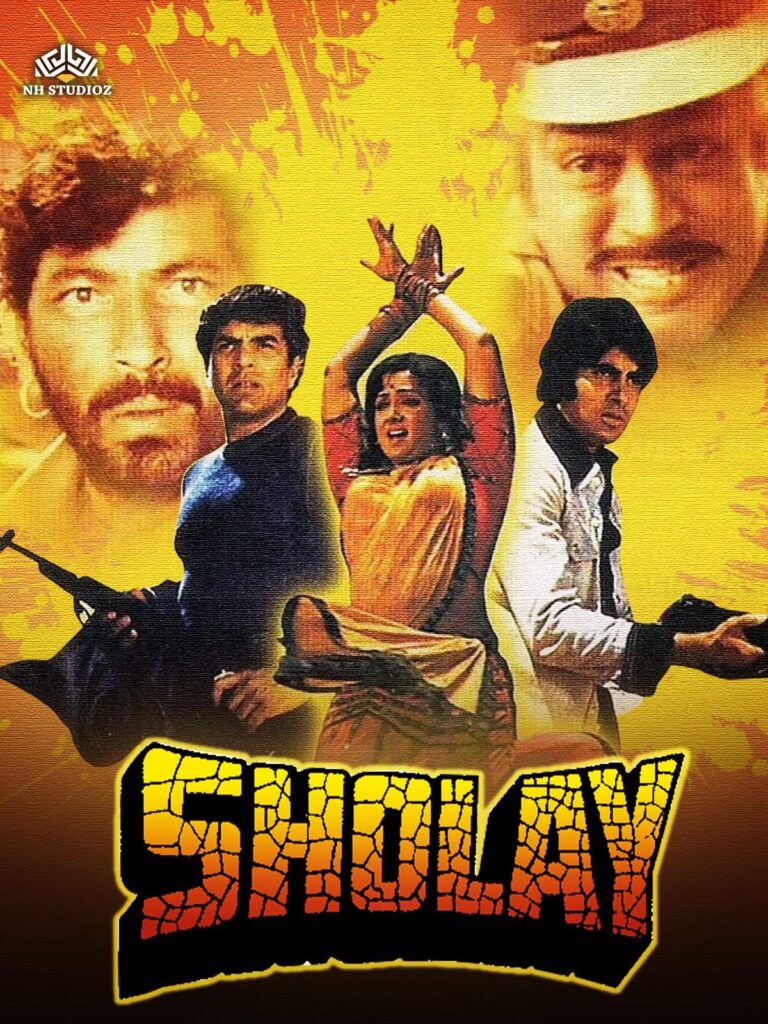

This is not to say that titles of single works have never been allowed protection. In Sholay Media and Entertainment Pvt. Ltd vs Parag Sanghavi, the case was filed against the defendants who proposed to release their film under the title ‘Ram Gopal Varma Ke Sholay’. One of the main questions was with respect to whether the film title could include the term “SHOLAY” and whether this could come under “passing off”. The court took note that the plaintiffs had obtained trademark registration for the terms SHOLAY, GABBAR and GABBAR SINGH, under several classes including classes 16 and 31. Additionally applications had been filed for registration of SHOLAY for various goods such as perfumes, video films, watches, leather goods, cleaning materials, clothing, toys, food items, and chewing tobacco. The fact that the term SHOLAY had been “continuously and extensively used over a long period of time spanning a wide geographical area, coupled with vast promotion and publicity” was found to prove that SHOLAY enjoys “an unparalleled reputation and goodwill”. The court noted the similarity in plot, characters, use of dialogues from the original movie gave the overall impression that the defendant’s movie was a remake of the original film. Accordingly, the court issued a permanent injunction restraining the defendants from “passing off” their film or other production, using the mark SHOLAY or any other deceptively similar mark, or by making use of characters or names thereof, from the plaintiffs’ work, or in any other similarly deceptive manner. Another case in point is Vishesh Films Pvt. Ltd. v. Super Cassettes Industries Ltd where the court held the use of titles “Tu Hi Aashiqui”, “Tu Hi Aashiqui Hai”, and “Aashiqui” by T Series to be deceptively similar to Vishesh Films’ trademark based on phonetic and conceptual similarities between the two.

These cases illustrate how protecting a film title is not an easy endeavour but not impossible. The possibility of the court upholding protection is more likely if the words used in the title are not generic or if the title is so iconic that it is instinctively linked to the work by the public.

Retro Revival: the new trend of bringing back the old

Recent times have seen a new trend in films: the use of vintage hit songs, carefully placed in between the plot to stir nostalgia. Some examples include the “Maambatiyan” song in Tourist Family, “Kanmani Anbodu Kadhalan” in Manjummel Boys and “Kiliye Kiliye” in the recently released Lokah: Chapter One- Chandra. This love for vintage vibes is making appearance not only in songs but also in movie titles. A few notable films include Vikram (2022 and 1986), Godfather (2022 and 1972), Shaandaar (2015 and 1990). The audience response to old classics returning to theatres is a testament that this strategy is in fact working: a chance for Gen Z to get acquainted with classics and the filmmakers to reintroduce their films with the hope that they finally get the appreciation they deserved. All’s well until someone arrives with an intellectual property claim.

The question therefore is simple: is capitalising on the nostalgia factor by using someone else’s work, even if a title, legally permissible? The rights of the original creator and respecting his wishes to not associate his works, whether a film title or song, with another film of a different quality or intent, is called into question. Allowing reuse for commercial benefits without the creator’s consent could risk diluting the original work while an absolute bar on reuse could throttle creative freedom. The wiser course is not a rigid yes or no, but maintaining a careful balance, protecting creators without locking nostalgia away in a vault.

![A Blair Waldorf standalone is in the works !!!! The Queen of Upper East Side is going to have a sequel of her own, with the focus completely on her !

Like she deserves 🫶🏻🙇🏻♀️✨

What is your favourite Blair Waldorf moment from Gossip Girls ?

[Blair Waldorf, Gossip Girls, Sequel, Iconic, Pop Culture, Quotes, Icon, Queen Bee, Let The Raven Talk]](https://lettheraventalk.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)