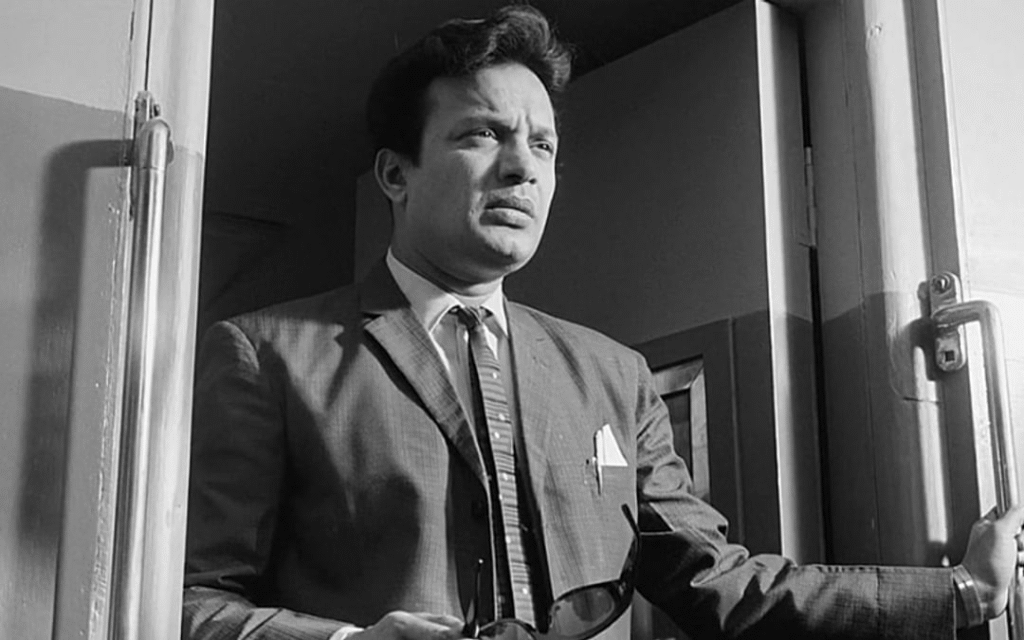

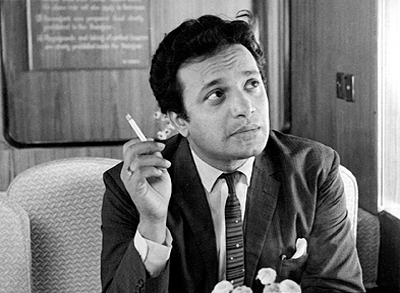

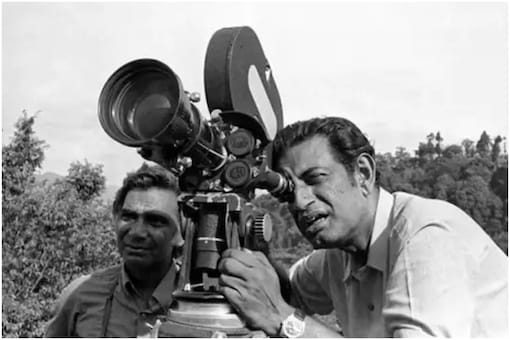

The Delhi High Court via a landmark judgement in the case of RDB AND CO. HUF versus HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED declared legendary filmmaker late Bharat Ratna Satyajit Ray as the first copyright owner of the 1996 Bengali film ‘Nayak’. Satyajit Ray who was the screenplay writer for the film portrayed the life of an insanely popular matinee idol, a brash, haughty young superstar riding the waves of popularity and enjoying it to the hilt. However as the story progresses the audience is grappled by the various layers of the film which are so rich and deep but at the same time expressed in such simple language that it is till date claimed to be one of the best works of the writer’s illustrious career.

Nayak is one of the only three feature films in Ray’s body of work that are not adaptations, and are original screenplays written by Ray himself. The story was further backed up by terrific performances by actors like Sharmila Tagore and Uttam Kumar which allowed the story to reach the vogue it deserved.

The facts of the concerned case deal with the issue of copyright ownership in the screenplay of a film provided that the author had been commissioned by the producer to write the screenplay.

Satyajit Ray was commissioned by R.D. Bansal to write the screenplay of and to direct the film “Nayak” and the same was accordingly carried out. After Ray’s death in 1992, Mr. Bhaskar Chattopadhyay novelized the screenplay and released the same on 5th May 2018.

The controversy arises between Mr. R.D. Bansal who claims to be the owner of the copyright and Mr. Bhaskar Chattopadhyay, who believes that the copyright in the screenplay was vested in Mr. Satyajit Ray and consequent to his death vested in his son Sandip Ray and the Society for Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives (hereinafter referred to as the Archives), of which Mr. Sandip Ray is a member. Accordingly, Mr. Chattopadhyay claims to have rightfully obtained the license to novelize the screenplay from Mr. Sandip Ray and the Archives.

SUBMISSIONS BY THE PLAINTIFF

According to the submissions made by Mr Bansal, as the producer of the film, he is the rightful owner of the copyright in the film as well as indirect, derivative and related rights associated with the film, at all times.

The plaintiff relies on section 17 of the copyright act which deals with the first owner of copyright. The attorney representing the plaintiff emphasizes that since Mr Bansal invested all monies in the making of the film and was solely responsible for its commercial release and commercial exploitation as well as single-handedly bore the entire risk of the commercial failure of the film. Mr Bansal was the producer, the worldwide distributor of the film and the first publisher of the film in 1966. Thereafter, Mr Bansal also invested in the preservation of the film. Accordingly, the attorney representing Mr Bansal tries to establish the fact that Mr Bansal had commissioned Mr Satyajit Ray in the capacity of a producer. One may say that through this an attempt was made to establish a “contract of service” between Mr Satyajit Ray and Mr Bansal.

It is highlighted that the defendant acknowledged Mr Bansal’s rights with respect to the film by formally, initiating communication to seek permission for the screening of the film Nayak at the launch of the impugned novel. The series of communication between the defendant and Mr Bansal, both disregarding each other’s copyright in the screenplay, followed by a worldwide launch of the novel led to the present suit.

The attorney of the plaintiff relies on the judgement of Thiagarajan Kumararaja versus capital film works (India) Private Limited, 2018, Madras High Court. He submits that as the story of the novel is identical to that of the film, the novel is effectively a copy of the film. “It was the film itself, therefore, which was being converted to pen and paper. There would be no distinction between the idea convey to the viewer of the film and the reader of the novel.” The word “copy” he submits in this regard has to be given a broad interpretation.

SUBMISSIONS BY THE DEFENDANT

The defendant made several submissions which disregarded Mr Bansal’s presumed rights.

According to the defendant, there is a difference between cinematographic film and its underlying works i.e. the script, the screenplay and the still photographs from the film. The right of a producer to a film is restricted to the physical form of the film and does not extend to the underlying works such as the screenplay or the script. Accordingly, Mr Bansal as the producer would have no separate copyright or right of use over the underlying works.

In order to substantiate its arguments, the defendant refers to section 13 (4) of the copyright act, according to which the copyright in a cinematographic film would not affect copyright in the underlying works, even if the underlying work constituted a substantial part of the film itself. A reference is also made to the definition of author in section 2 of the copyright act, which according to the defendant does not extend to underlying works with respect to a cinematographic film.

The defendant highlights that Mr Satyajit Ray had merely consented to write the script and screenplay on the basis of which the film came to be made. Such consent did not amount to any assignment of the copyright held by him in the script in favor of Mr Bansal. Any such assignment would have to be by a way of a separate agreement in written as per section 19 of the copyright act.

Accordingly, the defendant emphasized that the presumption of copyright by the plaintiff is contradictory to the copyright act and therefore should not be allowed to pursue the matter.

The defendant also relies on section 14 of the copyright act which defines “copyright”. It was submitted that the right to make a cinematographic film in respect of a literary work is a separate/independent right envisaged under section 14 (1) (a) (v). Through this, the defendant tries to differentiate between the other rights envisaged in section 14 of the copyright act and the right to make a cinematographic film in respect of a literary work.

By making this differentiation, the defendant claims that the only right which can be said to have been licensed by Satyajit Ray in favor of Mr Bansal is the right to create a cinematographic film and the other rights with respect to the copyright in the screenplay such as the right to novelize the screenplay continue to vest in Mr Satyajit Ray and post his demise with his son Mr Sandip Ray.

ANALYSIS BY THE COURT

Copyright in the screenplay is different from copyright in the cinematographic film:

According to the court section 13(1) deals with works in which copyright subsists. It clearly differentiates between the copyright in cinematographic films, and the copyright in original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works.

Therefore, the copyright held in a cinematographic film shall not affect the separate copyright in any work in respect of which, or in respect of a substantial part of which the film is made.

“If a cinematographic film is made in respect of a part of whole or another work in which separate copyright vests under section 13(1). The copyright held in the cinematographic film would not affect such separate copyright.”

The court clearly highlights that there exists no dispute about the fact that the screenplay of the film is entirely the work of Satyajit Ray and the producer contributed no part with respect to it. Even the film Nayak was the result of the directorial efforts of Satyajit Ray, Mr. Bansal is merely, the producer of the film.

In order to ensure that section 13(1) is attracted to this particular case, the court tries to analyze how the expression “literary work” is to be understood with respect to the copyright act. In the past courts have adopted an expansive understanding of the expression literary work.

For example in the case of Rupender Kashyap versus Jeevan Publishing House, the court held that the words “literary work” are not confined to “works of literature in the commonly understood sense, but include all works expressed in writing whether they have literary merit or not.” Accordingly even examination question papers were also held to be original literary works for the purpose of the copyright act.

Given the ambit of expression literary work, Justice C, Hari Krishna expresses that there is little doubt about the fact that the screenplay of the film Nayak is unquestionably a literary work for the purpose of section 13(1)(a). This means that the copyright in the screenplay as a literary work cannot be affected by the separate copyright in the cinematograph film (which unquestionably vests in the producer, Mr Bansal).

The first owner of the copyright in the screenplay is the author:

Finally, while answering to the question in whom does the copyright in the screenplay or film vest, the court refers to section 17 of the copyright Act, which makes it clear that the author of work shall be the first owner of the copyright in the work.

Considering that a lot of emphasis had been put on the fact that, the plaintiff had commissioned Satyajit Ray to write the screenplay and to direct the film, the court analyses on the existence of a contractual relationship between the two and the nature of such a relationship would determine the assignment of the copyright in the screenplay.

Accordingly, the court dwells in the question of difference between a “contract of service” and a “contract for service”. The difference between these expressions has been authoritatively explained in the judgement of the Supreme Court in Sushila Ben Indravadan Gandhi versus New Assurance Co Ltd. The use of expression contract of service, especially in the company of the word “apprenticeship” in clause (c) of the proviso to section 17 of the copyright act makes it clear that the clause does not apply to cases of a contract between equals in which one person contracts with another to render or service to him, such as in the present case, writing the screenplay for and directing a film. At the highest such a contract would be only a “contract for service” and not a “contract of service”.

Novelization is not adaptation:

Lastly, while dealing with the question if the novelization of the screenplay infringes on the copyright of the film, the court refers to section 14 explains the term “copyright as well as the definition of “adaptation” as defined in Section 2 (a). Accordingly the court deems that as long as the novelization of the screenplay does not “involve either abridgement of the screenplay or converting it into a version in which the story or action is conveyed, wholly or mainly by means of pictures in form of suitable for reproduction a book” it is not infringing on the copyright of the film.

Therefore, the court held the petition of the plaintiff to be dismissed.

![Demna woke up and chose violence!!!

Gucci Milan Fashion Week Fall 2026, Demna’s debut Runway ✨🙇🏻♀️💋

[Demna, Gucci, Milan Fashion Week, Runway, Fashion, Italy, Let The Raven Talk]](https://lettheraventalk.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)