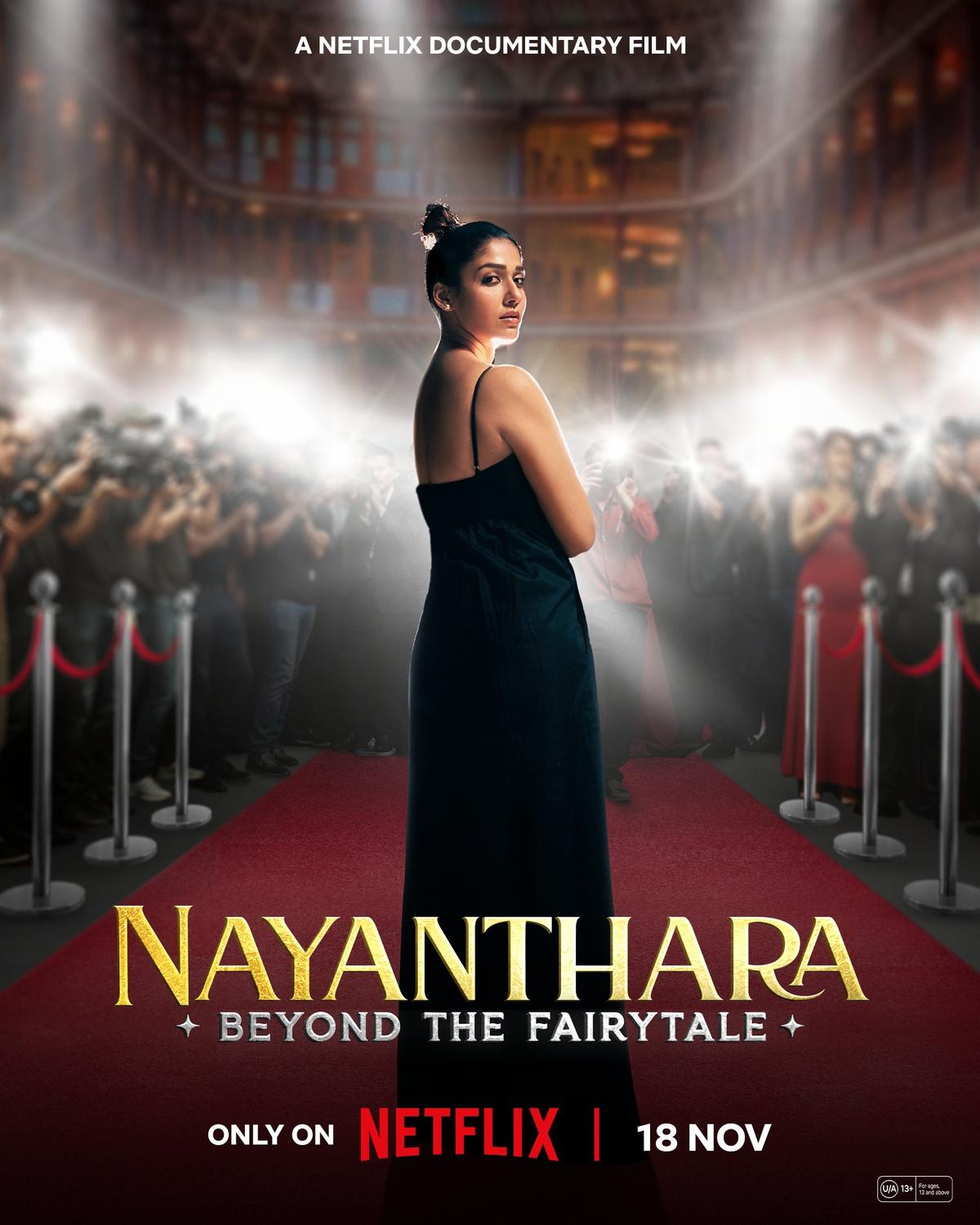

In a case that feels like a perfect storm of courtroom drama and cinematic spectacle, a seemingly innocuous three-second clip has triggered a ₹10 crore legal standoff between two of South Indian cinema’s most celebrated stars Nayanthara and Dhanush. The controversy erupted on November 18, 2024, mere hours after Netflix unveiled the trailer for NAYANTHARA: BEYOND THE FAIRY TALE, a docu-series chronicling the actress’s journey through fame, film, and personal milestones. The trailer, intended to be a heartfelt peek behind the curtain, quickly became legal ammunition when Dhanush’s production company, Wunderbar Films, issued a legal notice accusing Nayanthara of copyright infringement. The bone of contention? A few fleeting behind-the-scenes (BTS) visuals from the 2015 romantic-comedy Naanum Rowdy Dhaan, reportedly shot by Nayanthara herself during filming, and allegedly included in the docu-series without a mandatory No Objection Certificate (NOC). According to Wunderbar, not only does the use of these clips violate the copyright vested in the production house, but also the Artist Agreement signed by Nayanthara that assigns the rights to her performance even candid, off-camera moments exclusively to the studio.

Nayanthara, however, responded not with legalese, but with a sharp-tongued open letter accusing Dhanush of indulging in a vanity-driven legal crusade. She claimed she had, for over two years, actively sought the necessary NOC to legally incorporate clips, music, lyrics, and intimate moments shared with Vignesh Shivan her now-husband and the film’s director into the documentary. Her argument centers around the idea that the documentary is not a commercial exploitation of a film, but a portrayal of her life story, in which the making of Naanum Rowdy Dhaan and her relationship with Shivan are deeply intertwined.

As the legal crossfire intensifies, the case raises broader questions that go well beyond this celebrity showdown: Who truly owns a performance once the cameras stops rolling? Do production houses hold perpetual dominion over all content captured during a film’s shoot, including spontaneous, personal moments? And in an era where streaming platforms thrive on authentic, behind-the-scenes narratives, how far can creators go without tripping over intellectual property law?

This legal clash, set against the glamorous backdrop of the film industry, is shaping up to be a precedent-setting moment one that could redefine the balance between creative freedom, contractual obligations, and personal storytelling in the age of digital documentation.

THE RISE OF THE LADY SUPERSTAR

In the dazzling world of South Indian cinema, few stars have shone as brightly and consistently as Nayanthara, lovingly known as the “Lady Superstar.” Born as Diana Mariam Kurien on November 18, 1984, in Bengaluru, she has built a remarkable career that goes far beyond just being a screen icon. With over 80 films across Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada languages, Nayanthara’s journey from newcomer to powerhouse performer is nothing short of inspiring. Her life story is one of bold choices, breaking stereotypes, and proving that women can not only hold their own in a male-dominated industry but also lead it.

The Early Spark

Nayanthara made her debut in 2003 with the Malayalam film Manassinakkare, and from the moment she appeared on screen, audiences took notice. Her natural charm and expressive performance hinted at a star in the making. Not long after, she entered Tamil cinema and starred in hits like Ghajini and Raja Rani, where she showed her range from emotional drama to strong, independent characters. While many actresses were typecast, Nayanthara stood out by choosing roles with depth and meaning. She wasn’t just the love interest she was the story.

Why Her Journey Matters

What makes Nayanthara’s rise so iconic isn’t just her impressive film list it’s the way she changed the game. Being called the “Lady Superstar” wasn’t just a title it was a statement. She proved that women could headline major blockbusters, bring audiences to theaters, and still hold creative power in an industry traditionally run by men. Her success opened the doors for many more female actors to be seen as more than just side characters. But it wasn’t easy. Like many women in the public eye whether in business, entertainment, or social media Nayanthara faced intense criticism, unwanted scrutiny into her personal life, and impossible beauty standards. And no, being famous doesn’t mean you sign up for that kind of treatment.

Her biography doesn’t just list films it tells the real story behind the spotlight. It reveals the struggles, the sacrifices, and the strength it takes to survive and succeed in the film world. From pushing back against patriarchy to staying true to her vision, Nayanthara’s story is one of fierce determination and grace. It’s not just a tale of fame it’s about fighting for your dreams, staying grounded, and redefining what stardom means.

And just when her life seemed like a carefully scripted success story, a three-second video clip shot on her own phone became the center of a ₹10 crore legal battle proving once again that in Nayanthara’s world, even the smallest moment can become a headline. Her journey, both on and off the screen, continues to inspire and remind us that true superstars don’t just follow the script; they rewrite it.

WHO REALLY OWNS THE CAMERA ROLL? UNDERSTANDING COPYRIGHT, MOVIES & BEHIND-THE-SCENES FOOTAGE IN THE SPOTLIGHT

To understand the dramatic legal fallout between South Indian superstars Nayanthara and Dhanush, we need to look beyond the headlines and into the legal script that governs the film industry copyright law. This isn’t just a fight over a three-second behind-the-scenes (BTS) video; it’s about who owns what when it comes to content in cinema’s ever-expanding universe. In India, copyright for films is governed by the Copyright Act, 1957, and it draws some clear though sometimes complicated principles.

According to Section 2(f) of the Act, a cinematograph film includes any visual recording made by processes similar to cinematography including digital or video recordings. Section 14 grants the copyright owner a set of exclusive rights over that film like reproducing it, adapting it, distributing it, or licensing it to someone else. So far, so good. But who holds that copyright?

Here’s the classic movie twist: in most cases, the producer is treated as the default copyright owner of the entire film unless a contract says otherwise. That means even if an actor delivers a performance of a lifetime or a lyricist pens a hit song, the rights to those elements often vest in the producer unless the creators have written agreements carving out or protecting their own IP (intellectual property). This might seem a bit unfair, given that a movie is a patchwork of creative inputs from many talented professionals. But legally, the producer who finances, manages, and releases the film typically holds the final rights.

That said, the law does protect individual contributions when contracts allow for it. This has been made clear in key rulings like RDB & Co. (HUF) v. HarperCollins Publishers(2023). In this case, legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray had been commissioned to write the screenplay and direct Nayak. Later, when the screenplay was turned into a novel, the producer RDB claimed full copyright over it. However, the Delhi High Court ruled that Ray, as the author of the screenplay, was its rightful owner because the script was a separate, original work not automatically part of the film’s copyright. The Court leaned on Sections 13(4) and 17, which clarify that copyright in a cinematograph film does not extend to the individual works (like the script or music) that form part of it unless there’s an agreement transferring those rights.

A similar situation played out in Saregama India Ltd. v. VELS Film International Ltd(2025)., where the song En Iniya Pon Nilave from the film Moodu Pani was used in another film without Saregama’s permission. While Saregama claimed rights through the original producer, composer Ilaiyaraaja argued that as the creator, he retained the rights to the musical composition. Ultimately, the Delhi High Court held that the producer owned the copyright in the sound recording and lyrics, but not necessarily in the musical composition, unless it had been formally assigned. Again, this reinforced the legal idea that films are made of many copyrightable components, each potentially with different owners.

So, where does that leave us with BTS footage especially a short, candid clip captured on someone’s personal phone?

This is where things take a modern, somewhat murky turn. A few seconds of behind-the-scenes video may seem harmless, but when those seconds are used in commercial content—like a Netflix docu-series they become potential legal landmines. The key legal question is: does this footage fall under the film’s official copyright, or is it an independent work?

Under Indian copyright law, the answer depends on who recorded the footage, on what terms, and with what intent. If the video was taken by someone not hired to create official content say, an actor or crew member casually filming on their own device and there’s no contract stating that such footage belongs to the producer, it’s unlikely that the producer owns it. In legal terms, this means the BTS footage may not be considered part of the “cinematograph film” as defined by Section 2(f), and the person who recorded it could be seen as the original copyright holder.

This idea aligns with the general principle that for a producer to claim ownership of a work, that work must either:

- Be created as part of the film’s production process, or

- Be contractually assigned to the producer.

So, in a case like Nayanthara’s, where she allegedly shot a brief BTS clip on her personal phone during the filming of Naanum Rowdy Dhaan, and the clip was not part of the final film, soundtrack, or marketing campaign, the law may recognize her as the owner of that specific footage not the production house. Unless Dhanush’s Wunderbar Films can prove that there was a prior agreement or contract covering such material, their copyright claim over that BTS footage might not hold up.

This sets up a fascinating legal dilemma that speaks to our content-heavy, social media-driven age: As actors and filmmakers constantly document their journeys through photos, videos, vlogs, and reels, how do we legally separate personal content from commercial property? And how much of what happens behind the scenes belongs to the producers and how much to the people actually living those moments?

The outcome of this high-profile dispute could shape future contracts and industry norms, especially as documentaries, biopics, and streaming platforms increasingly rely on personal, “authentic” footage to tell their stories. The law may need to keep evolving to keep up with how stories are told today sometimes, even in just three seconds.

DEFENCES AVAILABLE TO NAYANTHARA: FAIR USE AND THE “TOO TRIVIAL TO SUE” RULE

While Dhanush, as the producer of Naanum Rowdy Dhaan, does enjoy copyright ownership over the film, this ownership is not absolute. Under Indian law, especially Section 52 of the Copyright Act, 1957, there are certain exceptions to copyright infringement commonly referred to as the defence of fair dealing (also known as “fair use”). This provision allows limited use of copyrighted material without requiring permission, provided the use falls under specific permissible categories such as:

- criticism or review,

- reporting of current events,

- educational or research purposes, or

- use in the public interest.

1. Fair Use in the Context of a Biopic

In the present case, the three-second BTS clip used in the Netflix documentary Nayanthara: Beyond the Fairy Tale can be argued to fall under fair use, since the purpose of the documentary is biographical and non-commercial in nature. It aims to present the life and career of Nayanthara who, as a public figure, has starred in numerous films that are integral to her identity and public journey. Including a fleeting, candid moment recorded on her own device offers contextual background rather than commercial gain. Given this intent, the clip arguably qualifies as fair use for a critical or review-oriented depiction of her career and personal growth.

2. The ‘De Minimis’ Rule: When the Law Ignores Trivial Use

Another key defence available to Nayanthara is rooted in the legal principle of “de minimis non curat lex” which means “the law does not concern itself with trifles.” In copyright jurisprudence, this doctrine protects individuals against legal action for very minor or insignificant uses of copyrighted content.

This defence was solidified in Indian courts in India TV Independent News Service Pvt. Ltd. & Ors. v. Yashraj Films Pvt. Ltd. (2012), where the Delhi High Court created a five-factor test to determine whether the de minimis defence applies:

- a. Size and type of harm caused by the usage

- b. Cost of adjudicating the dispute

- c. Purpose of the violated legal obligation

- d. Effect on third-party rights

- e. Intent of the alleged infringer

Applying this framework to the Nayanthara-Dhanush case:

- Size & harm: The clip is a mere three seconds in a full-length documentary and does not form a core component of the show.

- Cost of litigation: The legal resources required to challenge this minimal use would far outweigh any real damage caused.

- Purpose of the obligation: The inclusion seems incidental and intended to narrate a real-life relationship and journey, not to commercially exploit the original film.

- Effect on third parties: There is no indication that the brief clip harms Dhanush’s or Wunderbar Films’ commercial interests.

- Intent: There appears to be no malicious intent; the use seems expressive and personal, rather than exploitative or infringing.

3. Supporting Case Law: Pop Culture Meets IP Law

Courts have consistently leaned on the de minimis doctrine when trivial or minimal uses are involved:

- In the same India TV case, using the line “Kajra Re Kajra Re” in a consumer awareness ad was found to be too trivial to constitute infringement.

- In Krishika Lulla v. Shyam Devkatta(2015), the Supreme Court reiterated that movie titles like Desi Boys are too insignificant to warrant copyright protection.

However, it’s worth noting that not all courts treat de minimis lightly. In Shemaroo Entertainment Ltd. v. News Nation Network Pvt. Ltd. (2022), the Bombay High Court emphasized the importance of obtaining explicit permissions, indicating a stricter interpretation of IP rights in media.

Taken as a whole, Nayanthara’s legal position is strengthened by both context and proportionality. The use of a privately shot, three-second BTS clip in a non-commercial, personal documentary intended to reflect on her career and relationship with director Vignesh Shivan may be deemed legally insignificant (de minimis) or permissible under fair use.

While Dhanush may argue unauthorized use and assert his copyright ownership, courts will likely consider the intent, scale, and impact of the footage. In the grand theatre of Indian IP law, this isn’t just about rights it’s about balancing legal protection with creative freedom in the age of docu-series, vlogs, and personal storytelling. After all, in showbiz, not everything that hits the screen needs to hit the courtroom.

In today’s digital-first entertainment world, where every frame whether part of a polished film or a casual behind-the-scenes moment can be monetized, the line between personal content and copyrighted material is blurrier than ever. The ongoing legal battle between actor-producer Dhanush’s Wunderbar Films and Nayanthara, the reigning “Lady Superstar,” is a striking example of this evolving tension. At its heart lies a seemingly minor detail a three-second video clip, recorded informally by Nayanthara on her personal device during the shoot of Naanum Rowdy Dhaan, which later found its way into her Netflix documentary Beyond the Fairytale. But that tiny moment has now triggered a ₹10 crore legal firestorm.

The key issue here isn’t just the use of a clip it’s the larger question of who owns what in the creative process. Producers are typically granted full ownership of the film under Indian copyright law, but extending that control to all tangential content, like BTS footage captured independently by actors or crew members, begins to tread into murky waters. Is a personal video, not commissioned or edited by the production team, truly the property of the producer? Or does it fall outside the scope of copyright protection for cinematograph films under Section 2(f) and 13(4) of the Copyright Act, 1957? If courts start to view such clips as infringing, it could set a precedent that chills future creative expression, especially for documentaries, autobiographies, and biopics that draw from lived experience and personal archives.

The outcome of this case may ultimately hinge on whether the footage is viewed as a legitimate, contextually relevant piece of Nayanthara’s life story, or as an unauthorised use of protected content. But regardless of which side the judgment favours, the case has already shifted the conversation in the industry. It signals a growing need for artists and production houses to negotiate far more detailed and forward-looking agreements ones that clearly define rights over ancillary and derivative materials, from outtakes and on-set vlogs to phone-recorded memories that may later hold commercial value.

In a content economy driven by virality and storytelling, everything is potentially a product and thus, potentially a lawsuit. This case is a loud wake-up call to the Indian film industry: protect your footage, define your rights, and don’t leave any frame uncontracted, especially when those very frames may one day end up in court. Because if you can stream it, clip it, or remix it you better be sure you own it.