Valentino Clemente Ludovico Gravani is called ‘The Emperor of Fashion’. Similarly, Chanel is known for its classic aesthetics and Dior admired for the timeless femininity of its design. It is suffice to say that luxury brands like these “aim” to represent affluence, elegance and the very intricacy and layered complexity of couture and high-fashion that we all love and adore.

However, what is also well-established are the often-occurring instances of luxury brands being involved in illegal and unfair creative practices at the expense of smaller niche brands that don’t necessarily have the fiscal or legal strength to protect their creative works or hold the ‘sharks’ accountable.

Dior and plagiarize? Yes.

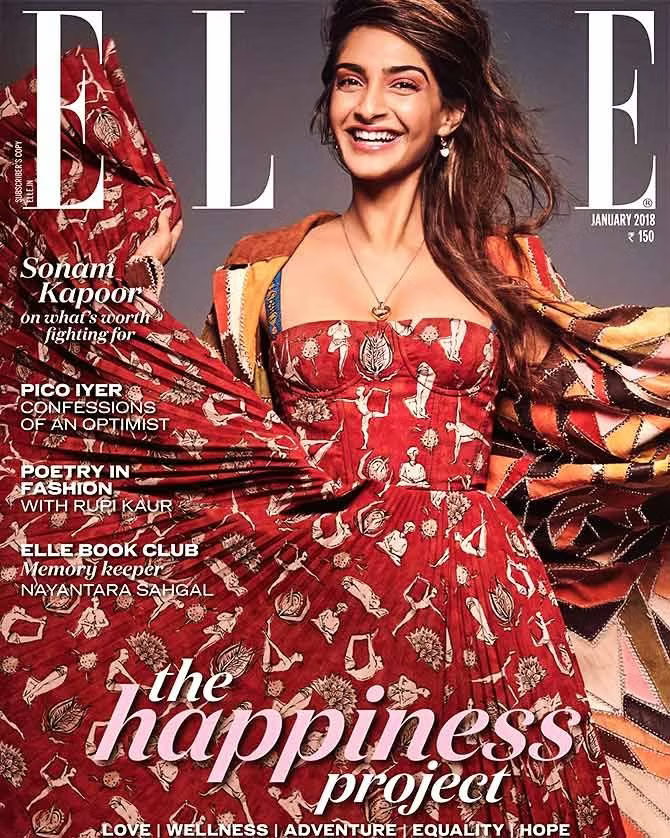

The luxury house Dior came under fire, when it released a design print on a red cotton dress. The dress was worn by Sonam Kapoor on the cover of ‘Elle’, but was revealed to be an exact replica of the yoga design that was hand block printed on garments created by People Tree, a company that produces handcrafted cotton clothing as well as jewelry and accessories; made using natural and biodegradable material whilst employing artisans from local communities with their rich traditional knowledge and skill. The infringement was called out on social media and subsequently, the brands decided to settle the matter out-of-court.

Are Chanel’s practices contradictory to their elegant reputation?

After buying certain original pieces from an independent Scottish designer for ‘research’, the designer had to witness the very same pieces resurfacing on the runway as a part of Chanel’s collection. While credits were given to the rightful source of designs only later, the entire transaction was dubious and far from honorable.

Another example with respect an Indian fashion house would be when the social media fashion connoisseur and watchdog, Diet Sabya, brought to light how Anita Dongre’s men’s collection, ‘coincidentally’ held striking resemblance to the designs made by students from JD Institute of Fashion Technology in New Delhi.

The instances of such creative infringements are numerous, however the consequences are far-fetching, violative and expensive.

A lawsuit of copyright infringement, misappropriation of trade secrets, and breach of contract, unjust enrichment and unfair competition was filed in the US District Court, New York this year, against the ‘Color Cool Couture’ house –Valentino S.p.A and its US subsidiary- Valentino USA Inc.

The suit was filed by Mrinalini, Inc., a New York based designer and manufacturer primarily involved in garment sourcing to fashion houses and designers spread all over the world.

PROLOGUE—

Business between the two parties’ i.e. Valentino and Mrinalini Inc. dates back to 2006 and the initial years of their agreement comprised of Mrinalini manufacturing goods employing their own original designs.

However, in 2014, there was a shift in the role undertaken by Mrinalini. The company went from being a designer to a mere contract manufacturer, supplying garments and other articles based on the designs provided by Valentino.

It was then that they entered into a ‘General Purchasing Conditions’ agreement which laid down that any dispute in connection to said agreement, its execution, interpretation, enforcement or validity will be referred to a sole arbitrator appointed by the Milan Chamber of Arbitration.

That being said, after the end of the agreement when the supply relationship ceded to exist in 2020, Mrinalini filed this suit.

According to Mrinalini, their general contractual relationship entailed that in a scenario where, Mrinalini was requested to provide a few sample designs and suggestions to Valentino, and the said samples were utilized by the latter for their own commercial business as a fashion house, then the former would be sufficiently compensated for the same.

It is the breach of this very condition that Mrinalini claims is outside the purview of the Arbitration clause of the Purchasing condition agreement and hence attracts the filing of a suit.

The company alleged that Valentino has copied their sample designs aka ‘swatches’ and incorporated them into their articles/designs without authorization. On top of this, they also pointed out that their specific manufacturing and weaving techniques including one claimed to be called “Intarsia” and another called “Sandwich Patch” that constituted trade secret essentials to their business had also been used and disseminated without authorization among other competitors, the end products of which were sold to make a profit. The fashion house also engaged in unfair competition, according to Mrinalini, when it “took complete and original products from Mrinalini and passed them off as its own, both on runways and in stores,” which the textile company says “is sometimes referred to as ‘reverse passing off.’”

These claims for the basis of the dispute at hand and the suit filed by Mrinalini Inc. against the fashion giant.

Valentino’s primary motive in opposing the suit was to move for its dismissal. They asserted that the dispute is to be resolved through arbitration, as per the arbitration clause in the ‘General Purchasing Conditions’ agreement. They urged the court to either dismiss the suit or stay the proceedings and order for arbitration, as per the exercise of the doctrine ‘forum non conveniens’ which means “a court has the discretionary power to choose not to exercise its jurisdictional power if the dispute is better suited to be heard by a different court”.

THE BONE OF CONTENTION—

Is the dispute under the purview of the Arbitration clause of the above-mentioned ‘General Purchasing Conditions’ agreement?

Mrinalini contended that firstly, the dispute at hand itself did not relate to the above-mentioned ‘General Purchasing Conditions’ agreement and neither does it fall under its purview. This is because, there was no agreement to arbitrate these copyright infringement and trade secret claims under the US law, against Valentino S.p.A. and Valentino U.S.A.

In response to this, Valentino primarily argued that the arbitration clause in the Purchasing Conditions Agreement is broad in its language of defining what amounts to a dispute. The counsel representing Valentino stated that the question of ascertaining as to whether the dispute at hand is arbitrable as per the Agreement or to be tried as a suit can itself amount to a ‘dispute’ that is to be addressed by the Arbitrator themselves.

Valentino also argued that the same Purchasing Agreement puts a prohibition on Mrinalini from obtaining intellectual property rights as the latter agreed to not register, or attempt to register, in its name any “trademark or design or other intellectual property rights” connected with the Agreement, and promised to transfer and assign free of charge to Valentino S.p.A. “all intellectual property rights which may be acquired by the Supplier by reason or as a result of the Agreement.” Mrinalini’s intellectual property infringement claims are therefore also argued to be subject to the Agreement, thereby claiming that the intellectual property rights infringements don’t stand.

Finally, Valentino pointed out that there happened to be the term ‘Materials’ in the Purchasing Agreement which includes in its ambit ‘all materials supplied to Valentino’, therefore arguing that the products which were the subjects of the alleged copyright infringement as per Mrinalini, would be subject to the Purchase Agreement.

COURT’S DECISION—

The court reasoned that, since any dispute associated with the Purchasing agreement, connected to its execution, interpretation, enforcement, validity etc., would come under the ambit of the Arbitration, and given that the dispute involves the question of ‘enforcement or interpretation’ of the Purchasing Agreement, the question of arbitrability is assigned to the Arbitrator to decide, automatically.

The language in the arbitration clause also happens to be broad and inclusive, entailing words like ‘any dispute’, and therefore is deemed to be flexible enough to include disputes over the arbitrability of an issue.

The court concluded that it was suitable to order a stay on the suit until the question of arbitrability is determined by the Arbitrator so that, in the event where arbitration is deemed unsuitable for the dispute at hand, the claims can proceed before this court just where it was left off.

And the court observed that on the very face of it, the purchasing agreement explicitly states that the question of arbitrability ought to be decided by the Arbitrator and this bolsters their stance to order a stay on the current suit.

Therefore, the court decides to grant the motion to compel arbitration of the claims brought in by Mrinalini, as per the Purchasing Agreement.

While some aggrieved brands, like Mrinalini manage to call out and seek action against the infringing and violative creative and trade practices of the bigger fish in the sea, thanks to the power of social media, legal awareness and fiscal strength; there also exists, unfortunately, a large portion of creators and designers in the fashion space who don’t’ have the same means and fortune.

The network of local artisans, weavers, designers and suppliers from indigenous communities, smaller localities, emerging artists, or even students- with little to no awareness and financial strength don’t necessarily stand a fair chance against the ‘big fish’ infringers. This is where it becomes imperative for the enforcement of Intellectual property rights to take place across the strata of creators in fashion, right down to the smaller scale ones too.

As for the current case, there are two sides to it, like a double-colored reversible dress. One being the arbitration of the dispute, which can prove to be fair or can succumb to Valentino’s affluence. The other outcome being, the dispute is declared as not arbitrable and it proceeds to be tried at the NY District Court.

As a third party, the writer vehemently prefers the latter, and wonders if such a broadly worded agreements should even be allowed in the first place? The verdict is yet to come out on this apparent case of “infringement”, but what do you think about it?

![A Blair Waldorf standalone is in the works !!!! The Queen of Upper East Side is going to have a sequel of her own, with the focus completely on her !

Like she deserves 🫶🏻🙇🏻♀️✨

What is your favourite Blair Waldorf moment from Gossip Girls ?

[Blair Waldorf, Gossip Girls, Sequel, Iconic, Pop Culture, Quotes, Icon, Queen Bee, Let The Raven Talk]](https://lettheraventalk.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)