James Bond is more than just a spy – he’s a brand, a cultural juggernaut with a legacy spanning over seven decades. Created by British author Ian Fleming. Bond first appeared in Casino Royale (1953), a novel that presented the sharp-witted yet ruthless secret agent known by his codename, 007. Fleming, a former naval intelligence officer, infused the character with real-world espionage tactics and a signature sense of style, setting the stage for a franchise that would go beyond literature and dominate global cinema.

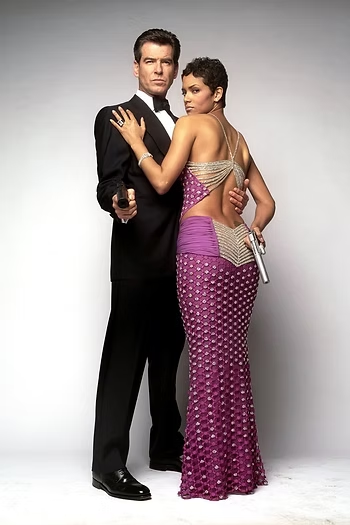

From Sean Connery’s debut in Dr No (1962) to Daniel Craig’s gritty reinvention in No Time to Die (2021), Bond has evolved with the times while keeping his signature elements intact: fast cars, high-stakes missions, and, of course, his iconic introduction, “The name’s Bond, James Bond.”

He has survived assassination attempts from megalomaniacs, nuclear threats, and even Die Another Day (somehow). But now, the world’s most famous spy faces an adversary like never before. No more suave introductions. No more 007 branding. No more martinis, shaken or stirred, under the name that defined cinematic espionage. That’s exactly what’s at stake in a new legal battle that could strip the world’s most famous spy of his own identity.

The James Bond trademarks are controlled by Danjaq, the company that has overseen the franchise’s commercial and licensing rights since its earliest days. Danjaq was founded in 1962 by producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, who secured the rights to Ian Fleming’s character and played a climactic role in shaping Bond’s cinematic legacy. For decades, Danjaq has safeguarded the franchise’s trademarks, maintaining their exclusivity across films, merchandise, and branding.

Austrian businessman Josef Kleindienst, founder of the Kleindienst Group, which claims to be the largest European property developer in the United Arab Emirates, has filed ‘cancellation actions based on non-use’ in the UK and EU. He argues that Danjaq hasn’t used certain Bond-related marks in commerce for at least five years. If successful, this challenge could leave some of the franchise’s most iconic trademarks up for grabs, including James Bond 007 and the legendary “Bond, James Bond” catchphrase.

It’s an audacious move, but does it stand a chance? And more importantly, even if Kleindienst wins, can he claim 007 for himself?

This blog examines the legal parameters of the James Bond Trademark Dispute that will shape the outcome of this case, assessing the strength of Kleindienst’s claims, Danjaq’s defences, and the broader implications for entertainment trademarks.

The Battle Over Bond: Can 007’s Name Be Taken?

Kleindienst’s cancellation actions target distinct trademarks, including ‘James Bond 007’, ‘James Bond’, ‘James Bond: World of Espionage, “Bond, James Bond”, and ‘James Bond Special Agent 007’.

These trademarks are more than just words. They represent decades of cinematic history. The iconic introduction, “Bond, James Bond,” was first spoken by Sean Connery in Dr. No (1962), during a high-stakes casino scene that cemented 007’s signature charm. Meanwhile, ‘Special Agent 007’ traces back to Ian Fleming’s original novels, where Bond’s double-O status signified his license to kill, granted exclusively to MI6 agents who had completed two confirmed assassinations. Over the years, these phrases have become synonymous with the world’s most famous spy, shaping the franchise’s brand identity.

He has identified precise classes of goods and services where the marks allegedly remain dormant such as ‘Models of Vehicles’, ‘Computer programs and electronic comic books’, and ‘Electronic publishing and design’. Kleindienst Group is a luxury real estate and hospitality company behind ambitious projects like The Heart of Europe, a $5 billion resort development on Dubai’s artificial islands. Given his focus on high-end experiences and branding, securing rights to Bond-related trademarks could fit into a larger commercial vision such as themed developments, luxury experiences, or even digital media ventures that capitalize on the name’s global recognition.

If these marks are cancelled, Danjaq could lose exclusive rights to them, opening the door for others, potentially including Kleindienst himself, to claim or repurpose them. This isn’t just about merchandise; Bond’s entire commercial identity, from branding to licensing deals, could be compromised. The ripple effect would extend beyond legal battles. The prospect of the world’s most famous spy losing control over his name is one that fans and the entertainment industry will find difficult to accept. Bond movies have never been just about the action, they are about the feelings they invoke, the legacy, and a world that his fans have always trusted. Losing these trademarks will lead to dilution of his identity, opening the door for off-brand spin-offs, inconsistent storytelling, and a Bond universe that feels disjointed rather than timeless. Fans aren’t just invested in the name; they’re invested in everything it represents.

Trademark law operates on a fundamental principle of ‘use it or lose it’. This means that a registered trademark must be actively used in commerce for the goods and services it is registered under. ‘Commercial viability’ refers to the trademark’s active role in the marketplace, signifying that the mark is not just legally registered but also effectively used to identify and distinguish goods or services in commerce. This ensures that the trademark maintains its significance and value to consumers. The idea that its trademarks could be erased simply because some categories aren’t used daily is legally and commercially flawed.

For Bond, that means more than just existing in legal registries; the trademarks must be seen in films, stamped on merchandise, or woven into commercial ventures that reinforce their market presence. This makes the trademark dormant, and as per the trademark law, dormancy is a death sentence.

If the trademark owner fails to do so for a continuous period (typically five years) it becomes vulnerable to cancellation. The rationale behind this rule is to prevent trademark owners from hoarding without using them, which could stifle competition and limit market access for other businesses.

As brought to light in this case, certain Bond trademarks may have remained dormant for over five years, prompting Josef Kleindienst to invoke Section 46(1) of the UK Trade Marks Act 1994 and Article 58(1)(a) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation. Both provisions allow for the cancellation of trademarks that have not been put to genuine use within five consecutive years.

His argument is surgical. He isn’t broadly attacking all Bond-related trademarks. Instead, he has targeted specific categories where Danjaq’s commercial activity appears absent. This selective approach strengthens his case, as it focuses on demonstrable gaps in Danjaq’s trademark usage rather than challenging the Bond brand as a whole and increases his chances of success while still leaving room for strategic repurposing if he secures the rights.

For Kleindienst to succeed, he must prove that Danjaq has failed to meet the legal threshold of genuine use. Under EU and UK law, genuine use requires a trademark owner to show serious and consistent commercial activity that maintains or builds a market presence. Occasional, symbolic, or minimal use does not suffice. Token use refers to superficial or strategically timed actions meant to preserve a trademark without any real commercial intent, such as sporadic sales or one-off licensing deals that do not contribute to brand recognition or consumer engagement.

Take Prada’s triangle logo dispute, where the EUIPO ruled that Prada’s sporadic and minimal use of its logo was insufficient to meet the genuine use requirement. The decision emphasized that trademarks must be actively used in commerce, not just retained through occasional or passive use. Kleindienst’s argument mirrors this, he claims Danjaq hasn’t commercially exploited Bond trademarks enough to maintain their protection.

Courts determine genuine use based on the Minimax decision, which evaluates whether the trademark has been used in a way that preserves its commercial viability. This principle originated from Ansul BV v. Ajax Brandbeveiliging BV, where the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) clarified that genuine use entails real commercial exploitation of the mark, aimed at maintaining or creating market share in the relevant sector. This means that even if Danjaq has technically used the Bond trademarks, it must demonstrate that such use was substantial and aimed at maintaining a real market presence.

Danjaq’s Defence: Shaken, But not Stirred

With just two months to mount a defence, every move will count. Given the precision of Kleindienst’s attack, exploring the strength of Danjaq’s possible defences becomes essential in determining whether Bond’s legacy remains untouchable or unexpectedly vulnerable.

- Genuine Use: Kleindienst’s argument hinges on the claim that Danjaq has not ‘genuinely used’ the contested trademarks in commerce over the past five years. However, proving non-use is harder than it sounds. Under UK and EU trademark law, ‘use’ is not limited to direct sales, it includes licensing, merchandising, and even promotional activities.

In Standard International Management LLC v EUIPO, the General Court of the EU clarified that advertisements and offers for sale can constitute genuine use of a trademark. Luxury brands like Omega (watches), Aston Martin (cars), Crockett & Jones (shoes), and N.Peal (cashmere sweaters) all actively market Bond-branded products. These aren’t occasional gimmicks—they are high-value collaborations that reinforce the Bond trademarks’ presence in commerce.

Even in categories like video games and digital content, Bond’s trademarks remain active. The upcoming Project 007 game by IO Interactive is set to continue Bond’s legacy in gaming. The idea that these marks are ‘unused’ ignores their widespread, ongoing commercial impact. Film-related trademarks are inherently unique because their usage cycles depend on production timelines, making continuous use impractical but not abandoned. Courts recognize that the film industry operates on production timelines that differ from other sectors, and they consider these industry-specific practices when evaluating trademark use.

In Inferno Films Ltd v. Revenue & Customs, the court recognized that intermittent but strategic film production activities could still demonstrate genuine use. Despite subcontracting, the company’s long-term filmmaking plans were acknowledged, highlighting how courts consider industry-specific timelines in trademark assessments.

- Residual Goodwill: Even if a mark isn’t actively used, residual goodwill can prevent cancellation. Courts recognize that some brands hold such strong consumer associations that reassigning their trademarks would create deception. Bond trademarks are so entrenched in the public consciousness that stripping them away would mislead consumers. Even in the absence of direct use, the association with Bond films ensures continuous commercial impact. James Bond is a multi-billion-dollar brand with decades of global recognition.

The Viacom International Inc. v. IJR Capital Investments, LLC case ruled that even a fictional name with no direct commercial sales can be protected if consumers strongly associate it with a brand.

- Bad Faith: Kleindienst’s plans to use “Bond” in a luxury resort suggest an ulterior motive. Filing a cancellation without an existing vying product indicates opportunism rather than actual commercial need. Under EU law, explicitly Article 59(1)(b) EUTMR, bad faith challenges, those filed not out of legitimate business need, but to seize a well-known mark, can be outright dismissed. If Kleindienst’s goal is simply to profit off a globally famous brand, his case could crumple before it even yields traction.

What happens if Kliendienst Wins?

Whilst examining the possible outcomes of the case, even if Kleindienst wins, he’d be met with a far greater challenge: navigating the legal and commercial minefield that still surrounds the Bond trademarks.

First, Danjaq can still oppose any new trademark applications. Just because a trademark is cancelled doesn’t mean it becomes public property overnight. Danjaq could argue that any new registration by Kleindienst creates consumer confusion, especially given Bond’s longstanding global recognition.

Courts have repeatedly recognized that well-known brands don’t lose their grip overnight. Maslyukov v Diageo Distilling Ltd reinforced that residual goodwill can linger long after active use has ceased, meaning a name with deep consumer recognition isn’t easily up for grabs. Courts have ruled in past cases that brands with strong public recognition can possess protection even if they haven’t been continuously used in a commercial sense.

In Fenty v Arcadia Group Brands Ltd, Rihanna proved that even without a registered trademark, public association alone can be enough to block unauthorized use through passing off. Bond isn’t just a name, it’s a multi-billion-dollar franchise with decades of cultural significance. This could lead to possible passing off or unfair competition claims against Kleindienst if he tries to use Bond trademarks in a way that misleads consumers.

Even if trademarks for “James Bond” were cancelled, the character, films, and branding remain protected under copyright law and merchandising agreements. For instance, the Bond character and logo remain copyrighted. Even without trademarks, unauthorized use could still be challenged under copyright law. Licensing deals protect Bond-related products. Even if Kleindienst cancels trademarks in one category, licensing agreements could prevent similar uses in others.

The Trademark Dispute That Could Change James Bond Forever

Kleindienst’s challenge exposes a weak spot in trademark law- one that major studies can’t afford to ignore. Unlike fashion or tech brands, film trademarks don’t operate on a regular sales cycle. Their value lies in new releases, licensing deals, and cultural relevance rather than daily transactions. Yet, under UK and EU law, five years of inactivity in a specific category can put a trademark at risk.

If this action succeeds, expect studios to rethink their trademark strategies. More aggressive licensing, deliberate merchandising, and possibly even legal reforms could emerge to prevent opportunistic cancellations. But cancellation doesn’t mean open season. Strong residual goodwill and consumer association remain powerful shields against unauthorized use.

The real takeaway? Entertainment trademarks aren’t just about commercial transactions but about maintaining ownership. Otherwise, the names, phrases, and symbols that define pop culture could become vulnerable to third parties looking to capitalize on their cultural cachet.

This case is a reminder that intellectual property protection requires active engagement. Studios and brands must not only register trademarks but also ensure they are visibly and consistently used in commerce to prevent opportunistic challenges. Whether James Bond remains exclusively under Danjaq’s control or sees a partial loss of its trademarks, the outcome will set a precedent for how legacy franchises safeguard their intellectual property in an evolving legal landscape.

As Bond himself might say, the game is far from over.